Economic Growth and Advertising: Downturn? What Downturn?

CEOs and CFOs from many of the world’s largest sellers of advertising have been speaking at an investor conference hosted by Morgan Stanley this week. Many of those individuals have talked about their relatively weak recent results while referring to the cyclicality of advertising, with references to how it is “tied to the economy” in context of “challenging” macro-economic conditions.

As one of a handful of people on earth who have studied these sorts of things on a full-time basis at various points in his career, I can offer a unique perspective regarding industry-wide relationships between advertising and economic data. I can also assess the state of the advertising industry in a manner that doesn’t always map to what CEOs and CFOs may convey - even with best of intentions - about the broader sector.

For context, when I was at Interpublic’s Magna in the 2000s, I rebuilt from scratch a data set of advertising in the United States going back to 1980, including quarterly data from the 1990s-on which covered multiple economic cycles. From that data I can conclusively state:

In the US there are strong correlations between advertising and economic activity. GDP is an “ok” single variable, but a better one is PCE (personal consumption expenditures) for the obvious reason that people buying “stuff” should relate to advertisers buying media.

A better model can be established if you include other factors, such as Industrial Production, which reflects manufacturers making “stuff” – a driver of spending that can be independent of consumer spending, although there is inevitably some auto-correlation with personal consumption as well.

When you include multiple factors, you stop thinking in terms of “advertising is x% of GDP (or PCE)” and instead think more accurately about how GDP or PCE or other variables contribute to advertising growth.

Advertising has a lower correlation with economic variables on a quarterly basis than it does on an annual basis. Moreover, concurrent relationships are stronger than lagging or leading ones. Put differently, advertising doesn’t follow or anticipate an economic downturn or boom: it coincides with these cycles.

As a more general rule, I also observed that economic variables are only a proxy for what actually drives advertising. The real driver is an economy’s “creative destruction,” or the tendency for an economy to replace old businesses with new ones with different characteristics. An economy primed to develop companies who operate in oligopolies that differentiate themselves via branding is much more likely to experience more spending on advertising than one which produces only monopolies or one which only produces small-scale, locally constrained businesses in perfectly competitive industries.

Later, at WPP’s GroupM, in collaboration with colleagues around the world I went through a similar process as the one I went through at IPG, and spent more time refining data sets for countries outside of the US. Correlations between economic activity and advertising over the course of multiple economic cycles were actually non-existent in many cases. Our best explanation for this was the aforementioned creative destruction issue, which didn’t happen to coincide with economic activity as measured by conventional metrics such as GDP or PCE in many places. This creative destruction issue also helped explain what likely went on in the US over the past decade, where a GDP or PCE-based model was increasingly unable to predict advertising, as so many new businesses emerged which were disproportionately dependent on advertising (especially via social media and e-commerce-based channels).

With the relationship between advertising and the economy clarified and out of the way, the next thing we need to do is actually look at the economy.

It has been notable to me when industry participants have referred to results from the fourth quarter of 2022 and implied that there was some kind of broad-based economic downturn in the United States. For practical purposes, this has not occurred, despite widespread perceptions of something different.

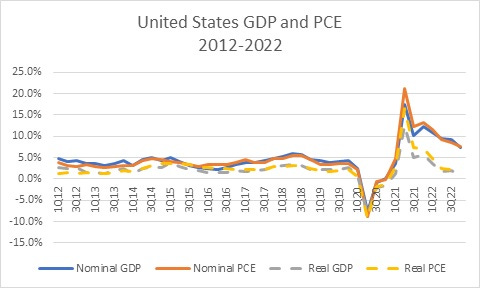

It’s true that there were two consecutive quarters of negative annualized real (excluding inflation) GDP growth during the first half of 2022, but during the first quarter the decline was due to a quirk in export numbers (which, critically, shouldn’t have much to do with domestic advertising). Putting aside that the right way to look at GDP when you are mapping it to nominal annual growth in advertising is to focus on GDP in nominal and year-over-year terms (which would have shown positive GDP in both quarter), PCE (the more important driver of advertising) was positive during that time however you looked at it.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

Looking forward, economists’ consensus has come around to the view that things aren’t likely to be too terrible for the economy this year. Looking at the variable we should care about the most, consensus tracked by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve via its Survey of Professional Forecasters calls for 1-2% annual growth in real PCE in the United States for each quarter during 2023. While that’s soft vs. most years in the 2010s, it’s not negative, and so long as inflation is in the low to mid-single digits, in nominal terms growth in PCE should be substantially higher than historical norms.

So we’ve established that there has not yet been a recession and that there isn’t necessarily going to be one in the year ahead. But you may still believe that there was a downturn in advertising during the most latter part of 2022, right? Actually, that didn’t happen either.

As I wrote yesterday, digital advertising was probably up by mid-single digits in the fourth quarter – 6% globally ex-China for the biggest five sellers of advertising, and I’d guess there was slightly more growth in the US alone. The third quarter saw closer to 10% gains for a solid high single digit growth rate in the second half of 2022. That covers around 70% of all advertising.

Looking at the next biggest medium, television, and focusing on the five largest traditional TV network owners – Comcast, Warner Discovery, Paramount, Disney and Fox – I can calculate that there were probably declines of around 5% for their domestic advertising businesses, excluding political advertising during the fourth quarter. The third quarter decline was more like a 10% fall, but this was due to a difficult comparable with the Olympics in 2021. Either way, with outdoor, radio and print probably roughly neutral overall (and off a small base by now), overall it’s likely that advertising in the US was up very slightly, and not down for both the quarter and the half.

Connecting economic activity to advertising trends is tricky in the best of times, and best considered over the course of many years rather than inside individual quarters. There could very well be softness in advertising during 2023 because of significant cuts in spending from certain categories, such as e-commerce-based marketers who drove so much of the growth we saw in last year’s first quarter (digital advertising probably grew by more than 20% during 1Q21), but an industry-wide decline is not what I would consider for a base case.

Overall, expectations for economic growth, imperfect as those expectations are, are likely the best variables to focus on when trying to anticipate advertising growth in any given period. But where those expectations are made I strongly recommend looking at full year rather than quarterly data. On this basis, I continue to feel confident that we’ll see solid, if unspectacular growth during the year to come.