The last week of August was another slow time in media-land, and there wasn’t going to be much of anything to summarize…at least until the very end of the week, as a potentially existential issue for the world’s largest owners of studios and TV networks was illustrated on a hastily scheduled call and presentation for investors hosted by Charter Communications.

Charter is the second largest cable operator in the United States - and by now almost equal in size to the largest, Comcast - with 15 million subscribers to its pay TV service, equal to approximately 1/5th of all subscribers in the country.

In the unusual, but highly insightful event, Charter’s management discussed its carriage dispute with Disney and described itself as having reached “the point of indifference under the current industry model.” In other words, they can claim to be credibly positioned to completely walk away from the traditional approach of distribution television-based content with Disney and everyone else, for that matter. Even if broadband access has been the flagship product from legacy cable operators since well before the pandemic, and as cord-cutting has been accelerating for the past few years, it was nonetheless remarkable to hear such a large distributor so explicitly articulate this view.

It's less clear that Disney is positioned as well as it needs to be in order to walk away. At the same time, it’s also not clear that they will be able to meet Charter’s demands.

So what is Disney to do?

Back in 2018, at the time when Disney announced its streaming strategy, I thought that the company’s aggressive embrace of a new content packaging and distribution model would serve them incredibly well from a strategic perspective in the long-run. But I also thought that margins would erode meaningfully, and permanently, which was a factor in my very out-of-consensus Sell rating on Disney’s stock. As investors have become all too well-aware in the past few years, margin erosion has played out as expected. What I was likely wrong about was the degree to which Disney itself accounted for the negative near-term financial consequences that would be required to achieve its ultimate goals.

In response to the pressures that the company ended up facing, some of Disney’s recent actions have demonstrated much more of a short-term focus than I would have anticipated. To the extent they continue to do so in context of the Charter dispute, Disney will inevitably find itself in a much worse position.

If Disney provides complimentary access to its streaming services for conventional pay-TV customers as part of their existing subscriptions (much as Charter is proposing in order to retain its role as a distributor of video services), it seems likely that Disney would lose many of the subscribers who today pay doubly for Disney’s streaming products. On the other hand, if Disney doesn’t do as Charter is asking and the two sides fail to come to an agreement, Disney will immediately lose a significant amount of high margin revenue – Charter was set to pay Disney $2.2 billion in 2023, equivalent to around a third of last year’s cash from operations, and significant advertising revenue would be at risk as well - although some of this would be offset as consumers who want Disney’s networks will shift their subscriptions to alternatives such as YouTube Live, Disney’s own Hulu, Fubo or Sling.

It's hard to imagine near-term upside from anything Disney might do to under the circumstances. However it’s also highly unlikely that the general dynamics of the industry are likely to change, regardless of what Disney and Charter do.

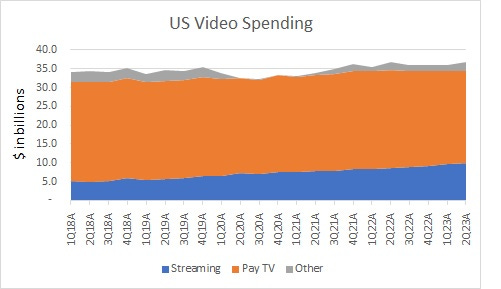

As I’ve been tracking consumer spending on video services over the past few years, US consumers has shifted spending away from conventional pay TV and towards streaming, with 15% of spending on video going to streamers in the second quarter of 2018 but 27% in the second quarter of 2023, while total spending has only increased by a compounded rate of approximately 1% per year. I would argue that as prices go up for streaming services, they will cause consumers to keep paying more for streaming, but perhaps churn away from those which fail to invest significantly in unique content and/or which aren’t used as much.

Source: Madison and Wall, DEG, BoxOfficeMojo

As prices rise for traditional pay TV, we’ll only see more cord-cutting, largely because the biggest streamers – especially Netflix and Amazon, which don’t have much of a stake in the traditional business model – will continue to offer tremendous value for money on their streaming services. More importantly, as consumers become more and more used to content in on-demand environments (and much of the best programming, too, as it’s unlikely that streamers will run their highest profile content on linear services exclusively), consumption will only continue to shift in that direction.

Ultimately, the right approach for Disney will be one which best connects to whatever they see as their long-term direction of the industry, and the profit margin profile of the business will follow. My guess is that the approach I originally imagined Disney pursuing, with massive investments in content in countries around the world and must-have status in a large number of consumer homes, is probably a better business than one which tries to balance near-term profitability while managing incumbent distributor relationships, if only because the most critical competitors they are up against are unlikely to be so-encumbered. Getting there will require much more financial pain than they’ve seen so far, but it will probably be worth the effort if they choose to pursue it.