Today we are releasing a new long-form publication commissioned by Google entitled “The Future Of Planning Is The Platform.”

The report builds on work we published previously (including one from 2023 entitled “The Medium Is The Mess”) and explores how marketers will plan their media budgets in a world where AI-driven platforms proliferate and potentially house a majority of marketer spending. The full contents of the document are included below, and are also available as a .pdf at https://madisonandwall.com/free-reports

Key takeaways include the following:

AI-based ad products are poised to proliferate and grow, offering the potential to eliminate friction in many of the processes that pre-determine many marketing budgets, especially within media.

Presuming that sufficient controls and transparency are enabled in these products, larger marketers will embrace them. As they do, there will be significant challenges in optimizing spending across them. Media mix models (MMMs) and Multi-Touch Attribution (MTA) tools will be important in helping with resource allocation decisions.

How marketers manage spending against customer journeys will be changed in this world, too. Marketers can potentially rely much less on simple and overly monolithic frameworks such as AIDA (awareness, interest, decision, action) and instead look to manage spending against a wider range of dynamic considerations inside of individual campaigns.

The Future of Planning Is The Platform

With Special Thanks to Individuals Who Provided Insights For This Project:

Pierre Bouvard, Cumulus Media

Paul Donato, The Advertising Research Foundation

Trevor Guthrie, Giant Spoon

Evan Hanlon, Choreograph

Joanna Lawrence, Havas Media Network

Elisa Lee, Google

Patrick Miller, Flywheel

Sue Unerman, Brainlabs

Jon Watts, CIMM

Paul Woolmington, Canvas

Commissioned by Google

Opinions expressed in this document are Madison and Wall’s and do not necessarily represent Google’s opinions or those of the individuals who participated in interviews for this project.

Overview

For as long as we can remember, claims such as “the next five years will see more change than the last fifty” always came across as hyperbolic to us. While it’s unlikely that such a claim could ever be universally true, when it comes to media planning and the management of customer journeys, it might actually be a reasonable assessment of what’s about to occur for marketers who lean into this era’s new possibilities.

But beyond exploring our own views, as part of our effort to explore how this world might evolve, we wanted to capture related ideas from practitioners with a wide array of perspectives, which sometimes disagree with the narrative outlined above, but mostly add a significant amount of nuance that help us consider how the industry might be impacted in the coming years by the increasingly common use of wide-reaching AI-based buying platforms in the future among large marketers.

We outline a wide range of related possibilities and consequences for the industry in the remainder of this report.

PART 1: SETTING THE STAGE

A Brief Historical Overview of Media Planning and the Customer Journey Framework

Since at least the early 20th Century, the concept of viewing marketing through the lens of “awareness,” “interest,” “decision,” and “action” (or “AIDA”) has been a dominant framework used to describe the customer journey that ties the introduction of a product through to its sale. AIDA was never the only customer journey that existed - it was just a simplified model that explained how products interacted with customers in that era. As a result, AIDA has been largely responsible for the strategies that historically underpinned media budget allocations. That means that marketers who have solely relied on this framework have arguably missed out on opportunities to engage with their customers. AIDA never contemplated factors such as customer service, user experience, distributor relationships, service, word-of-mouth perceptions, loyalty programs or other factors that help explain why customers make the choices they do.

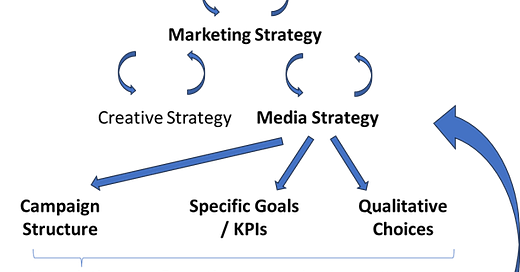

Meanwhile, media planning, which evolved within advertising agencies as a discrete function throughout the last century, was deeply related to the AIDA framework of customer journeys. However, optimization was only enabled with the rising availability of mainframe computers. Media planners would help inform how marketers would balance spending between goals and then establish a recommended budget mix in support of these efforts.

But planning wasn’t only about optimization: it was also about managing workflows. As marketers’ budgets became bigger, the benefits of operational specialization would have become more pronounced within both creative and media functions to reflect the distinct channels that existed. In other words, a marketer needed to consider well in advance of running a campaign how much money should go to “upper-funnel” objectives vs. lower-funnel ones and between, say, print vs. radio vs. television because each required different creative assets, workflows and timing associated with budget commitments. Planning was simply the process of establishing a justification for these different choices, including optimizations both within and across media types.

As media-focused agencies increasingly operated independently of their full-service brethren in subsequent years, the discipline became increasingly sophisticated. Data analysis, competitive analysis and other capabilities were folded into planning functions, but optimization against any of the aforementioned AIDA goals (defined in terms of reach for awareness or incremental sales for action, for example) remained central to this craft. During this era, as mass media remained dominant among consumers, the marketing goals for large brands remained heavily focused on awareness, with only limited spending allocations in support of interest, decision and action.

At the same time a myriad of performance-based (or “direct response”) marketers found novel ways to work with all kinds of media, looking to create signals where there were none (i.e. with dedicated 1-800 phone numbers) or otherwise steer their spending towards media which could offer tangible performance metrics. However, direct response remained something of a backwater for the advertising industry, far less prestigious than the brand-focused part of the business.

But then digital media arrived, and at massive scale as we progressed through the 2000s and 2010s. After making inroads among DR advertisers (some of whom became massive themselves), digital media made it easier than ever for historically brand-focused marketers to scale their spending on lower-funnel metrics. It wasn’t long until “outcomes-based” marketing and KPIs primarily focused on “performance” or short-term sales-related metrics became an increasingly common concept, capturing a growing share of budgets as the years progressed.

TRADITIONAL MEDIA PLANNING PROCESS ILLUSTRATION

Source: Madison and Wall

However, plans are simply tools which help inform the budget allocations that are ultimately made. While there was likely always a gap between what was planned and what was actually bought, that gap has probably broadened over the last decade.

To illustrate why, consider the increasingly common “joint business planning” process between digital media owners, agencies and marketers. A marketer’s planning team may identify that last year the optimal media mix was 40% TV, 50% digital platforms and 10% other, and that the new plan would be optimized next year with a 50%, 40%, 10% mix. In reality, the marketer might start out with a 30/65/5 mix and then distort that mix further because of subjective preferences (because marketers might perceive some media formats, spending choices or platforms more favorably than others) or because of commercial incentives from media owners (though preferred commercial terms, improved flexibility, special offers to get involved in novel trials or through other means). In this example, the marketer might easily wind up with a 25/75/0 mix by the time their campaign actually runs.

As part of this process, one of the most subjective choices has been how to allocate resources between upper-funnel and lower-funnel metrics. Although large marketers we have spoken to about this topic assert that they know the long-term health of their brands are of the utmost importance, they also acknowledge that their marketing teams are driven by internal incentives which tend to favor increasing spending on short-term performance.

The Introduction of AI Platforms

Before we continue, let’s now level-set on what is happening and about to happen with media platforms.

Over the past couple of years, many of the world’s largest sellers of advertising including Google, Meta and Amazon have developed AI-based advertising products named Performance Max (or PMax), Advantage+ and Performance Plus, respectively, which each have or should soon have the capacity to develop creative assets “on the fly” and then optimize spending across the different kinds of ad inventory each has access to. This development has capitalized on a few key trends that are broadly appealing to marketers of all sizes and kinds

A primary focus on specific, short-term oriented outcome-based KPIs, such as sales (at the expense of longer-term and more ambiguous or harder-to-define goals such as brand perceptions, as noted above)

The relative ease with which advertisers can use automation to reduce “non-working” costs

The improving quality of AI in both creative and media settings

While larger marketers have generally eschewed these products to date because of concerns around transparency of ad placements within the platforms, many other marketers evidently have fewer issues. In October 2023, a year after launch, Meta’s Advantage+ posted a $10 billion revenue run-rate during the prior quarter and in January 2025 revealed a $20 billion run-rate in the fourth quarter of 2024. Presumably the performance of this kind of ad product has been a primary driver: for example, Google has claimed that “advertisers who adopt Performance Max see an average increase of 27% more conversions or value at a similar CPA/ROAS. This is even when they already use broad match and Smart Bidding in their search campaigns.” Meanwhile, Pinterest claims its Performance+ requires “50% fewer inputs to get started,” illustrating the potential to reduce costs required to manage these campaigns. Given these commercial successes, it seems all-but-certain that others will proliferate as time progresses.

It also seems all-but-certain that platforms will provide marketers with more transparency and more controls. For example, Google has increasingly been adding more controls and reporting transparency to Performance Max based on feedback from advertisers. They recently announced improved keyword exclusions ("campaign-level negatives") and more granular conversion data in asset group reporting. We think such efforts will encourage large brands to meaningfully increase their use of these products over time, perhaps even allocating a majority of their spend through these products before long. To the extent those efforts are successful, we can also imagine TV network owners deepening their commercial relationships with digital sellers of advertising in order to attempt to better match the scale and performance capabilities that the largest digital platforms provide.

More broadly, because the incremental costs to produce different types of creative assets will be negligible and because different platforms are broadening the ways they service consumers, we assume that over time most platforms will establish or improve upon the ability to provide video, audio and text-based content alongside video, audio or text based creative assets for marketers. Different platforms will also retain many unique characteristics that can’t be found anywhere else.

In whatever direction the industry goes, many of the sources of commercial friction which historically forced the separation of functions, and which caused the establishment of many of its traditional processes and workflows will simply go away.

In this world, what happens to the concept of the marketing funnel, managing customer journeys and the discipline of media planning? In the remainder of this report, we explore these questions from our perspective and incorporate those of leading practitioners from within the industry who have extensive experience in media planning and related fields of media research.

PART 2: CONSEQUENCES AS WE SEE THEM

Given the history and likely path forward for platforms and marketers described above, we think the following will almost certainly occur:

Customer journeys can become more sophisticated

Martech and ad tech integration will become more important

Optimization across platforms becomes most important

Other issues will be harder to anticipate with as much certainty, such as the following:

What is the ultimate balance between performance and brand-building?

What is the role of agencies?

What is the role of creativity and creatives?

What is the role of the planner?

What other constraints to change exist?

Customer Journey Management Can Become More Sophisticated

To the extent our vision plays out, marketers should be better positioned to manage spending choices against a significantly broader range of customer journeys.

In the old world, most marketers could only manage against one type of journey: the AIDA framework described above. But as we anticipate the evolution of the industry, it should be possible for marketers to use the AI-based media platforms to improve how they spend against a much wider range of possible customer journeys concurrently or to use different frameworks for planning which account for all of the different ways that customers engage with products and brands, doing so in a dynamic manner.

One of these new approaches was proposed in a recent publication from Boston Consulting Group (also produced in collaboration with Google) which asserted that marketers “must plan their media buys based on what truly drives influence” with four key behaviors - streaming, scrolling, searching and shopping - representing core elements of modern customer journeys. In BCG’s framework, “influence maps” can look different for everyone, and campaigns should be customized at the individual level to account for those differences. Of course, this is only possible with sufficient investments in AI-based competencies and capabilities. A separate publication from BCG from December 2024 illustrates that marketers will need to establish “AI excellence across their organizations before (becoming) more sophisticated in managing their spending.”

Martech and Ad Tech Integration Will Become More Important

For many years we have observed the evolution of marketing technology, or “martech”. Around 2011 we can recall observing how one of the world’s largest email marketing software offerings attempted to mirror the broader customer journeys that their clients wanted to manage. We noted how much it mirrored the core service-based “product” one of the world’s largest creative agencies offered at the time. Both wanted to help manage the generation of demand, with one trying to do so primarily with automation and the other primarily with people.

As martech has evolved, the idea of managing customer journeys beyond simple awareness, interest, decision and action frameworks has become increasingly common, reflected in the marketing cloud software suites offered by companies such as Salesforce, Adobe and Oracle. But this software is typically managed very separately from the processes used to manage paid media. We think that with every passing year, growing numbers of marketers will want to manage these efforts together, if only because it should be much easier to do so as time progresses.

To the extent that occurs, we think there will be tighter integration between martech (with its focus on first party data) and ad tech (with its focus on third-party data) than exists today. Although marketers may need to do much of this integration themselves, together these sources will be used on any given platform – probably with some improved, if not perfect transparency in terms of ad placements – in pursuit of an optimized goal which will most likely be some outcome-based measure resembling incremental “sales.” (Readers should keep in mind that such measures are not always truly knowable, especially as most marketers do not control the full pathway of their distribution to end-consumers, or otherwise don’t have access to all of the relevant data.) High quality creative ideas – possibly developed with more investment than occurs into creative ideas now – would feed into these products, as the impact of good creative on media outcomes becomes increasingly evident.

From there, the wide range of customer journeys that different segments of consumers take would all be accounted for in this optimization exercise, at least within any one platform. Whatever the KPI and available budget, optimization within any one platform should become easier than ever before.

Optimization Across Platforms Becomes Most Important

Now consider the process of allocating resources for media.

In a world where every large platform can provide video, audio and text at minimum (and offer other unique capabilities that work towards similar goals for marketers), the biggest challenge - and most critical choice for the sake of efficiently pursuing any given goal – is figuring out how to optimize spending across platforms.

Beyond the joint business planning process that can lead to money getting peeled away and returned with opportunities getting added or removed, it may become harder than ever to identify what platform caused what outcome, at least without ongoing experiments or attribution products that distinguish the impact of different kinds of digital platforms (rather than digital as a stand-alone medium). Agencies may be relied upon more than they are now for this capability because of the benefits of experience they gain across many different kinds of clients and different kinds of campaigns.

Marketing mix models and multi-touch attribution models, whether operated by the marketer or the agency will be increasingly critical support tools, too. They will be key tools helping marketers who need to attempt to quantify the relative impact of different platforms. Although marketers will be increasingly open to using MMM and MTA tools provided without charge by all types of media owners, marketers will likely devote greater resources to using these tools, especially when they are provided by media owners of all kinds to help justify campaigns with them. Notwithstanding their limitations, this may lead to a marketplace of tools which all tell slightly different stories to marketers about what the sources of outcomes are, causing even more work for marketers (and agencies) looking to understand causes and effects in media campaigns.

At the same time, subjective or other commercial factors will still impact why marketers spend with individual platforms. For example, it’s not hard to imagine a future where one of the digital platforms secures exclusive rights to broadcast (or stream) the Super Bowl. Beyond the cost for the game’s specific ad inventory, any marketer who would want access to that inventory could be required to make incremental budget contributions to the host platform in order to ensure their brand’s advertisements run in the game.

Because it will be difficult to gather placement (or spending) data from within the platforms, optimization will mostly occur at a high level although it should improve with time as platforms offer marketers more controls and transparency into the “black boxes.”

Performance Goals vs. Brand-Building

It’s clear why “performance” has taken off in recent years. We’ve written about it extensively in the past, and noted above how the incentive structures that marketers set in place for themselves determine spending choices, even at the risk of damaging the long-term health of marketers’ brands.

But another factor pointed out in our interviews provided another reminder about a driver of this focus: highly sophisticated A/B testing should be easier, cheaper and faster than ever on these platforms, and the cost of experimentation should drop significantly. There should be more incrementality data than ever before to work with.

While seemingly everyone appreciates the primacy of “performance” and short-term goals (whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing is separate), practitioners we have spoken with for this study still held mixed views about whether or not the use of reach and frequency metrics will go away in the world that was laid out. Arguably reach and frequency will increasingly become table stakes for the largest platforms who tend to get the first look at a marketer’s “wallet,” much as the most important TV networks historically didn’t have to compete on this basis and were always best positioned to capture the marketer’s first dollars.

However, to the extent that a marketer truly cares primarily about sales or similar metrics, one interviewee suggested that if a marketer can get the same reach on two channels, but only one has closed-loop capabilities, the entity who can provide a closed-loop solution may see a disproportionate share of the marketer’s budget. Extending this argument, it explains why retailers are better positioned to secure traditional TV network or CTV inventory and resell it to their clients rather than the other way around. It’s more likely true than not that marketers try to optimize for both brand and performance, but when push comes to shove, they will tend to pick performance. Towards these ends, several years from now this premise explains why marketers in categories who sell everything through retail channels could get all of their reach needs met by retailers. Advertising budget shifts could follow.

Who Will Provide Attribution Tools?

In this world, it seems very likely that there is significant value to be generated by helping marketers figure out how to allocate resources across platforms. While MMMs and MTAs will be among the main tools, their power-users - typically specialists who are likely employed by agencies – will become increasingly important. Agencies will also employ many of the specialists who are most expert at aggregating and exploring the data that is necessary to build the models which inform marketers choices. Differentiation of analysis could very well become a defining point of differentiation between agencies.

More generally, marketers may become more reliant on marketing mix models or other attribution products than they are now. But where it could get interesting is if marketers continue reducing their “non-working” spending and exhibit a growing preference to not pay for these attribution products. As this occurs, the opportunity for everyone who doesn’t currently offer an MMM or an MTA tool – agencies and media owners alike – may find new opportunities to do so without client concerns around the conflict of interest of “judging ones’ own homework.” Marketers seem to overlook it now when it comes to using the attribution tools provided by the largest platforms, and we think they will be increasingly willing to do the same when it comes to other media owners and agencies.

What is the Role of Creativity and Creatives?

From the creative side, specialists will be highly sought after if they are able to “seed” AI-based media products with novel or impactful ideas. A common refrain from our interviews emphasized that nothing drives good performance (or any other objective) like great creative work. There are many other interesting issues to consider which are much less certain:

Defining “effective” for creativity is difficult (although becoming far more common as time progresses and with sufficient availability and use of relevant tools).

As platforms evolve and mature, each will still respond differently because of their mix of advertising assets. However, when those assets are similar, will each of them respond similarly to the same creative “seed” assets? Or will learning how to prompt different platforms differently with different creative assets cause a meaningful change in performance from one platform to another? Presumably this will depend on what assets the marketer brings to the table and the scale of ongoing investment each platform makes in its own capabilities.

Presuming that the very best marketing ideas will come from humans for the foreseeable future, there’s still a question of degree. Do we need creative assets from the world’s very best and most creative professionals to see better performance? Or will run-of-the-mill-good do well enough? One idea put forward in our interviews was that big new ideas won’t ever be properly testable and it’s necessary to introduce new “genetic material” into these platforms to get the most out of them.

How much less creative work will be required in this world? Presumably there will be fewer people with greater talent who will have an outsized impact, especially considering the reduction in amount of work it takes to bring an idea to fruition, which should help to free resources up Agencies (and marketers) will end up with the same or greater numbers of employees as new functions are established and grow.

Will bad creative permeate? As it will be easier than ever for a marketer to create their own ads, in a world where ads that are a quarter as effective but cost a tenth as much, that could be deemed a favorable evolution of the business for marketers On the other hand, it’s also possible that creative becomes better if marketers and platforms find the opposite, with reduced spending and improved outcomes.

What Is The Role of The Planner?

Arguably, one can’t opine on the future of media planning without doing as much on the future of media planners. In our interviews we discussed the separate but often intertwined roles of planners and strategists, who are often responsible for similar capabilities, depending on the agency group. Their objectives include finding ways to take advantage of the platforms’ array of offerings or to make sure that spending is thoughtfully done. That thoughtfulness could include a high degree of focus on client competitive analysis, for example, or a deep understanding of consumers’ relationships with brands and how best to connect with them. The value from this role is in looking holistically at all of the choices a brand might make.

Unfortunately for planners, for many brands the “good enough” may be better than the perfect, and so it’s not hard to imagine that most marketers will rely on the platforms they work with to provide at least some of these capabilities. Planning is already separated from buying by virtue of its theoretical / idealized approaches vs. activities that are more transactional and thus relatively more essential to activating client spending.

Still, it’s equally possible that the role of strategists and planners could evolve further given the range of ways they can add value. First, they should be on the frontlines of figuring out what the right campaign goals should be. And then especially in assessing offline activities – sponsorships, outdoor advertising, in-car radio, etc – and identifying optimal mixes across those channels, this function can be particularly helpful. For all of this to play out, planners may need to upskill for their roles to thrive, especially as the volume of data involved expands and the importance of not only analyzing it, but explaining it becomes more and more important.

What Other Constraints to Change Exist?

Beyond the issues described above, two other topics came up through interviews we conducted for this report.

First, there was some skepticism expressed about whether or not marketers would, in fact, make budgets shift in the manner described above for many reasons. For one reason, in digital media, targeting is often very flawed and inaccurate because of bad underlying data. Moreover, the “identity” data you get from on-boarders can be very “smushy” according to one of our interviewees, at least anywhere and with anyone who doesn’t have “closed-loop” data. Data fidelity might also be negatively impacted by privacy rules which restrict a platform’s ability to use some data in support of the performance goals described above. On the other hand, we also note that in the “least-bad alternatives” business of advertising, sometimes using the only available data is better than having none at all.

Separately, stakeholder management was raised as a whole other issue to consider. Sometimes marketers simply want to keep doing what they always did - changes in processes are politically hard, and often costly, too. Similarly, marketers often have benchmark data points to beat in order to satisfy the needs of their procurement teams. New approaches to assessing media costs for effectiveness may need to be developed as well.