US Agency Revenue Forecast And Industry Overview

5.4% Underlying Growth Expected in 2023, Similar Mid-Single Digit Expansion Should Persist For Years To Come

Ahead of the week when the Cannes Lions are held and the global advertising industry concentrates its attention there, it’s a particularly good time to focus on the current state and future trajectory of the advertising agency sector.

US Advertising Agency Revenues Should Grow By 5.4% On Underlying Basis During 2023. Although global agencies had a strong 2022 to build upon the immediate post-pandemic boom in 2021, independent agencies grew even faster. An extensive review of industry-wide data within the United States shows a similar trend was in place over the prior decade as well, revealing an industry that is arguably healthier than even its optimists understand it to be.

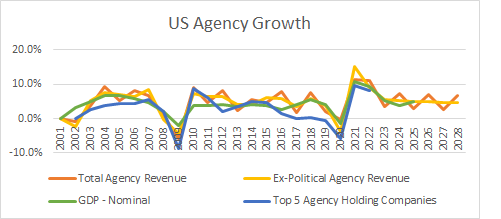

To the extent that the factors driving growth in the 2010s should continue and even accelerate slightly, partially offset by weakness in many traditional functions, underlying growth for agencies in the United States (excluding political advertising agency-related activity) should amount to approximately 5.4% during 2023 with an estimate of a 2% impact from political agency activity. All-in, growth might only amount to 3.4% according to my forecast, although this compares to total growth of 11.0% in 2022

As has been the case in recent years, reported organic growth within the region for the industry’s largest players should come in below the underlying figure of 5.4% – likely consistent with the global guidance that most agency groups have provided at around 3-5% – for a number of reasons. Most generally it is because growth can be faster for smaller agencies whose entrepreneurial practitioners may better capitalize on the ever-changing ways in which marketing adds value to companies. Scaled experiences applied to idiosyncratic marketer needs and the negligible amounts of capital required to start a new business in this space further supports the growth of smaller firms. This is not to rule out opportunities associated with scale: the largest agencies should be able to provide many services at significantly lower prices or with significant value-adding factors when they organize in a manner that allows them to do so. As well, holding companies who are particularly skilled at hiring, managing and retaining talent across their organizations and who are effective at cross-selling can also realize benefits from scale. Larger agencies can also benefit if they have previously invested well against favorably-positioned types of agency businesses or if they simply get “lucky” with a wave of momentum-driven new business wins.

Looking forward, underlying sector growth for agencies should hold up at around 5% each year through 2028, roughly consistent with average growth for agencies over five, ten and twenty-year periods of time in the past, and similar to nominal GDP growth in the coming years.

Source: Madison and Wall, Company Reports, US Census Bureau

Re-Assessing the Past: What Does Industry-Wide Agency Data Show? Sector Grows With the Economy, Not Holding Companies. Before formalizing a perspective on the future it’s important to have an accurate view of the industry’s historical trends, as continuations or discontinuations of past events will impact any future-facing model.

A dominant view in the latter half of the 2010s was that agencies meaningfully under-performed the broader advertising industry to which they were historically tied, and thus were becoming somewhat disconnected. The five biggest global integrated agency groups’ US (or North America) revenues grew organically by an average of only 0.5% between 2016 and 2021, 1.9% between 2011 and 2021 and 2.4% between 2001 and 2021. By contrast, data from WPP’s GroupM showed growth for ad revenues generated by media owners averaged 8.8%, 5.3% and 2.5% over similar periods of time. Consequently, large agencies’ correlation with media owners’ ad revenue growth was relatively low over the 20 year period, with an R2 of under 0.4.

While there are many factors that help explain these outcomes, such as increasing competition from consulting or IT services firms, heightened cost pressures from the largest marketers (especially packaged goods manufacturers) and outsized growth from emerging marketers who may not have historically relied upon external agencies, any assessment focusing solely on the largest agency groups was always going to be incomplete.

Towards these ends, I’ve now reviewed, aggregated and re-organized data from the US Census Bureau covering traditional advertising agencies, media agencies, PR firms and direct mail service providers within the United States on a like-for-like basis for the period between 2001 and 2021, the most recent year for which that data is available. From the data we can see that there is nearly three times as much agency-related activity vs. looking at the largest holding companies alone, with growth rates averaging 5% annually. Bi-annual “lumpiness” in historical growth rates coincides with national election cycles, roughly matching the trends we can see in media owners’ ad revenues due to political advertising. Politicians and others focusing on political issues typically use specialist agencies which generally don’t compete with other agencies, and so it’s important to attempt to isolate them in order to assess underlying trends.

More generally, although Census data has its methodological limitations, such as the manner in which individual types of businesses might be categorized and any sampling challenges, tracked growth mirrors trends observed in the broader advertising industry for media owners as monitored by GroupM, IPG’s Magna and others. It also happens to mirror revenue growth over the period 2011-2021 for more than 50 like-for-like independent agencies whose revenues have been tracked by Ad Age in their annual agency reports. Indeed, if we look at other Census data we can see much faster employment growth from agencies with between 100-499 employees than we can from agencies with more than 500 employees. For further confidence, consider that if we exclude an estimated figure for political agency-related activity, during the period between 2001 and 2021 agency industry growth and GDP correlates with a 0.7 R2, with only a slightly lower correlation for media owner ad revenue. As a counter-point we can see employment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics which shows much slower growth for the industry, but this divergence can be explained by the rising prevalence of offshoring alongside the increasingly global nature of the business.

With this data, excluding estimated political advertising agency activity, revenues for agencies expanded by a compounded average growth rate of 4.7% between 2016 and 2021, 5.0% from 2011 to 2021 and 4.5% for the period between 2001 and 2021. These figures are similar to growth in GDP and PCE over the 2016-2021 period although slightly higher over longer time-frames. However, agency growth as calculated here still comes in below media owner ad revenue growth in the 2016-2021 period although these two activities grew at a similar pace over the 2011-2021 period as described above. Incidentally, agencies significantly outperformed media owners when we include the first decade of this century as a massive decline in media during 2008-2009 was not mirrored by the agency sector.

What Does The Data Mean? Marketers Have Spent More on Agency Services Than Many Perceive As Large Agencies Lost Share In Recent Years. There are at least two big implications from the data captured here. First, it turns out that marketers’ spending on services grows more in-line with spending on paid media than might have previously been thought, and very much in line with economic growth. It’s certainly the case that large brands are reducing their spending in many places, such as traditional creative services from legacy advertising agencies, but evidently either they are making up for it with spending elsewhere, or newer emerging marketers are driving a lot of the growth by increasing spending with independents. Larger brands are certainly shifting a lot of their spending into different kinds of marketing, including experiential activities, influencer-related activity, retail media and various forms of business transformation, so it’s entirely possible that what we see in the data reflects a gain in the “share of wallet” that independents have relative to the large holding companies.

Second, we can point to meaningful share losses by the largest agencies in the US. Looking at the six biggest global players, the group’s share fell from 40% of agency activity in 2011 to 33% in 2021. Why this happened is open to interpretation. It’s possible that their core customer base of large and globally-oriented marketers grew their budgets to only a limited degree relative to other marketers, although I’m doubtful this drove the bulk of the underperformance. It seems more likely that marketers shifted spending elsewhere. To the extent this occured, did it happen because large agencies failed to anticipate or invest sufficiently in client needs? That’s certainly a strong possibility, as we know creative agencies generally stayed focused on their traditional services for much longer than they probably should have, even as marketers were shifting towards fewer, cheaper and faster development of creative assets given the primacy of social media platforms. On the other hand, we could also suggest that the largest agencies were very focused on capital efficiency and returns of capital at that time, which required ongoing margin improvement and a reduction in invested capital in the business. It’s possible that reduced organic growth was an consequence of that focus, whether intentional or not.

Of course, a business that isn’t growing is dying, and so whatever was intended, the consequences were real. Still, agencies did seem to generally revert towards a focus on data-driven top-line growth immediately prior to the pandemic (illustrated by acquisitions of Merkle, Epsilon and Acxiom by each of Dentsu, Publicis and Interpublic, respectively), which paid off last year, as growth continued beyond the 2021 V-shaped-recovery-based rebound. However, it’s worth noting that the largest 30 independent agencies still outperformed the biggest global agency groups by several percentage points during 2022, based on my analysis of those entities.

What Will Happen In The Future Solid Mid-Single Digit Growth This Year And Beyond, Supported By New Revenue Streams. Looking forward from 2022, 2023 seemed likely to be another period with relatively-high inflation (which has the effect of boosting advertising budgets) alongside underlying growth for the world’s largest advertisers’ core businesses (ditto). At the same time it was also quite likely that the first half would involve difficult comparables because of unusual growth following the pandemic, supported by low interest rates which could not persist. Six months into the year, these trends appear to be playing out mostly as anticipated.

The largest agencies have unsurprisingly guided towards global organic growth ranging from 3-5%. If this played out as anticipated, it would probably represent another year of under-performance vs. the broader industry’s underlying (ex-political) level as growth for independents will probably come in faster. As a crude proxy, headcount growth as tracked by Linkedin for the 30 largest independent agencies – probably amounting to $10-15 billion in revenue collectively – grew by 4% globally, around the same as the largest holding companies’ organic revenue growth rates, although the independents faced significantly harder comparables, and so it seems likely that performance differences will probably become more significant as the year wears on.

Looking at where the growth is coming from in terms of product offerings, data asset businesses which combine with data services should continue to contribute to growth for media agencies, much as IT services and adjacent activities should contribute to growth for legacy creative agencies. All types of agencies benefit from an increasing focus on commerce, which represents another area ripe with opportunities for growth.

Getting more specific in terms of modelling growth expectations within the American agency industry, I presently assume the following about different types of agencies, revenue streams and growth this year and in years ahead:

PR agencies (around 20% of the industry) should grow roughly in line with their post global financial crisis / pre-pandemic average level of 4.9%. Over the past couple of decades, PR agencies have performed in line with the broader agency industry, with event management and media relations stagnating, but non-traditional revenues demonstrating increasing importance. There shouldn’t be any reason for these trends not to continue. As with media, fragmentation is generally favorable for PR because it requires more labor to accomplish goals using this channel.

Stand-alone media agencies should be able to grow their core businesses by a slightly faster pace vs. PR, as the rise of data asset and service-related activity, media fragmentation, performance and commerce-related trends directly benefit media agencies by requiring more specialist labor, including programmatic activity, which despite the role of automation typically requires more people rather than fewer to manage a given budget than was the case in earlier eras. Efforts to drive “performance” represent another underlying source of growth because they open marketers up to alternative compensation models and because they require more specialist labor to identify cause and effect (especially true in the near future when third-party cookies, still a key source of monitoring “performance”, are deprecated everywhere).

Direct mail agencies (12% of the industry) should continue to serve an important purpose, but I don’t anticipate any growth and consequently model out a forecast that looks similar to the category’s pre-pandemic expansion rate of essentially 0. These kinds of agencies have been and will likely continue to be laggards (they are collectively roughly the same size now that they were ten and twenty years ago), as their core skills are increasingly embraced by other types of agencies, or have otherwise been folded into those agencies already. Nonetheless, so long as direct mail remains an important component of the overall advertising industry – it still represents nearly $30 billion in annual spending in the United States – there will surely be room for these types of businesses to operate.

Among other types of agencies – mostly traditional advertising agencies with legacies built around creative services – which combine to account for 60% of the industry, I assume much more tepid growth vs PR or media as soft conditions for functions such as creative ideation and production are more than offset by growth in design, experience and IT services which support all of the above. Those which have increased their focus in these areas or who have incorporated elements of creativity across a broader array of marketers’ consumer-facing activities – in-store kiosks, for example – are better positioned to experience ongoing growth, even in a world where their core capabilities are increasingly commoditized. Towards those ends, it’s not unreasonable to assume that AI will produce a headwind to growth for many businesses in the sector, especially those who provide commoditized services such as simple copywriting or generic video-based content for various marketing needs. However, if we consider how much “creative” work is already produced by AI-based tools – especially in social media environments – and note the consequences that have already played out, it would seem that there is only so much more damage to be done, especially as those types of agencies have already invested significantly in various forms of automation in recent years. To the extent the agencies most likely to be impacted continue to invest in people who can manage AI-based capabilities and who can socialize ideas with their (human) clients, the downside of new technology is limited. Overall, I assume low single digit growth for this group of agencies towards the end of the time horizon modelled here.

In addition, I think that principal-based trading and managed services are poised to contribute meaningfully to agency revenue growth in coming years, as marketers are demonstrating an increased desire (or at least preference) for situations where the costs of labor required to manage campaigns are bundled with media in one form or another. To be sure, not all and possibly most large brands will choose not to use these offerings, but substantial numbers of them will. If we assume that all of these sorts of solutions (including principal-based trades made by holding companies’ media arms or ad networks, barter trades and managed services provided by stand-alone pseudo-agencies) equated to something like 5% of all media at present and further assumed a 30% margin on gross sales, a 15% growth rate in media traded this way would convert into an approximate 1% tailwind for net revenue growth for the industry, which is what is assumed here.

The above approach leads to underlying growth that averages around 5% each year, and coincidentally roughly mirrors likely GDP growth in nominal terms. Beyond that underlying growth, variances of around 2% up and down should occur each year to reflect spending on agencies who focus on political advertising.

Overall, the agency industry appears well-positioned for a positive outcome in years ahead. Whether the widely-understood narrative about them will be equally positive remains to be seen.